Commercial Fishing

Mother & Fisherman

XTRATUF | MAY 10, 19

I remember going to the dock as a little girl to visit my father and grandfather and watch the boat being offloaded, trying to stay out of the way and avoid all the bickering and bantering coming from the crew. Trap fishing in Rhode Island, especially in the springtime, and especially for a fishing family, is all-consuming. The big boat, along with three long workboats and a small skiff in tow, leave the dock at 6AM and “steam” to the trap sites, not far from the dock at Sakonnet Point. The crew spread out among the workboats, and “haul twine” shoulder-to-shoulder, hand-over-hand, until the fish rise and boil to the surface and get bailed onto the big boat. Once back at the dock, the catch - butterfish, squid, scup, fluke, sea bass, striped bass, to name a few - get shoveled off the boat onto a conveyor belt, where it is sorted, weighed, boxed, iced and shipped by tractor trailer loads, mostly, to the Fulton Fish Market. This process can go on for months on end, with long hours, and no days off. If my mother, two brothers, and I wanted to see my father and grandfather this time of year, we had to go to them.

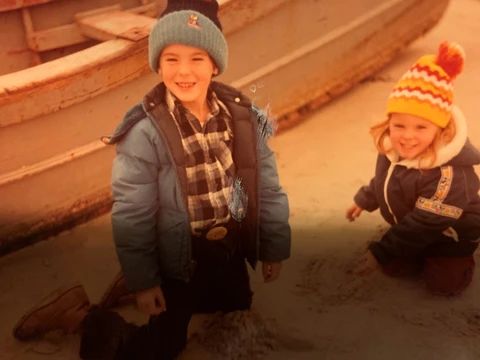

Corey with her older brother, Luke.

My younger brother, Miles’s earliest memory of fishing is of my dad jumping off the dock onto the boat with him and landing in fish, waist-deep. Luke, my older brother, recalls one of the old-timers giving him a dogfish, which he proceeded to put a leash on and take for a walk down the nearby beach. I mostly remember the endless fish talk and work that seemed to overflow into our home and backyard: the hallway of fishing boots, and fishy work clothes; the pungent smell of pan fried cod liver - a smell, once smelled, never forgotten. There were boats being built or painted in the backyard, buoy swings instead of swing sets, and forts made from lobster pots. I remember The Rolling Stones’ album “Let It Bleed” blasting out of the kitchen window as my dad stripped nets hung between the pear trees.

I had been fishing for about six years before my son, Finn, was born in 2002, and, later, my daughter, Isley, in 2006. I wasn’t sure how I was going to balance motherhood with fishing, but parting from either did not seem to be an option or a thought I could bear. As a fisherman, during our season, I was not going to have any time-off. I probably wasn’t going to be the parent cheering them on from the sidelines, crafting and volunteering at their schools, available to carpool, or be there for play dates, (thank goodness for my husband). Sleep-deprived and nursing, I idyllically imagined having them at work with me: a job and culture of hard work with a nautical language all its own that can feel foreign to an outsider; a job where there is literal beauty everywhere if you look and listen: sunrises, where the rays come through the clouds, reflect off the water, and make you feel like you are in a painting, leaving you in a warm, pink embrace; I wanted to share the excitement and anticipation of hauling the nets, where every day is different, not knowing what we would catch. I wanted to watch them learn the same old knots, stories, and legends that we all grew up hearing from the bow of the boat, as we headed in.

I used every baby carrier they made at the time - the front carrier, slings, and wraps, for when they were tiny and the Northeast wind blew. I would wrap a thick blanket around us and wear an oil jacket for extra warmth and protection. I had the hip carrier, when my shoulders couldn’t take the front carriers, and backpacks as they got older, I’d cover with a poncho and attach an umbrella. There were lots of nursing breaks, runny noses, and watery eyes. Sleeping babies often got passed around when my back couldn’t take it; Uncle Miles would wear Isley as she napped and he sorted fish. Fish totes made handy cradles and an empty ice vat was a quick, safe, place to put them down when needed. Finn’s first sentence was “beeeep, beeeeep, beeeep,” the sound the forklift makes when it’s in reverse and he loved helping on the conveyor belt, standing on a fish tote, surrounded by a bunch of protective old men. The old Portuguese ladies that would buy fish, would slip them dollar bills, sweets, and pinch their cheeks. As they got older, along with their cousin Olivia, Luke’s daughter, they’d help shovel fish off the boat, and would take more and more trips on the boat to help haul the traps. This was summer camp: the fishing boat and dock was their playground, and Grandpa was camp counselor.

Corey with her children, Finn and Isley.

I always think of Mother’s Day as being the height of my fishing season. Traditionally, my husband, Rob, and the kids will come out fishing or they will meet me at the dock when I get in, with fresh coffee in hand. I realize, especially now, Finn (16) and Isley (12), spending time with them, while they pursue their own independence and interests, is fleeting. I find myself begging and bribing them to come work with me just to see and spend time with them. I’m often rushing to their schools, carpooling, or cheer practices and games, straight from work: still in my XTRATUF boots and work clothes, fish blood splattered on my face and fish scales in my hair because I haven’t looked in a mirror all day - trying, but knowing a squirt of hand sanitizer probably isn’t going to do much. It’s not all calm seas and picturesque sunrises; it’s exhausting yet rewarding, and its far from glamorous, but I wouldn’t change a thing.

Corey Wheeler Forrest

Instagram: @fishandforrest

United States

United States

Canada

Canada

United Kingdom

United Kingdom